3Rs Stimulus Fund: multi-organs-on-chips replace laboratory animals

4 years agoBas van Balkom works as a researcher at the UMC Utrecht, in the Nephrology and Hypertension department of the Internal Medicine and Dermatology division. He is aiming to make complex organs-on-a-chip available for testing experimental therapies. They could replace the use of laboratory animals.

The title of your project is ‘MOOI!’, which in Dutch spells a word meaning ‘beautiful’ or ‘great’. What do the letters actually stand for?

They stand for ‘Modellen voor Onderzoek naar Orga(a)n(oīde) Interacties’, or ‘models for research on organoid interactions’. Studying the interactions between organs came out of a kind of gridlock. Animals are complex beings, but they aren’t human. The human cell models we use for in vitro studies are human, but they lack the complexity of an organism. What we aim to do is to develop combinations of human cell models, in order to achieve a greater complexity. This will enable us to simulate the interactions between human organs in the lab. That’s an essential step towards being able to establish the effectiveness and any side effects of potential therapies.

Doesn’t animal testing give us sufficient evidence?

Unfortunately not. Which means that many animal experiments are actually pointless. Animals differ from people in too many ways. Often, the proportions between their organs are different. They process some substances differently as well. And their immune systems often turn out not to represent ours very well. Also, with humans there are often side-effects that you can’t simulate in an animal. For example, I can cause kidney damage in an animal, and observe that it responds well to a given medicine. But the human using that medicine may be overweight or have diabetes: you can’t observe those side effects in the animal. And the other thing that often happens is that the medicine has already been absorbed or broken down somewhere else in the body before it even reaches the target organ.

That raises the question of why all research on medicines isn’t being done in vitro yet.

There’s still an extensive set of requirements for getting a medicine to the market. There are a number of standard assays that have to be carried out on animals for any candidate therapy. Some things simply can’t be found out working in vitro in the lab, like whether a given substance causes cancer.

You’re aiming to expand the possibilities of in vitro research. How?

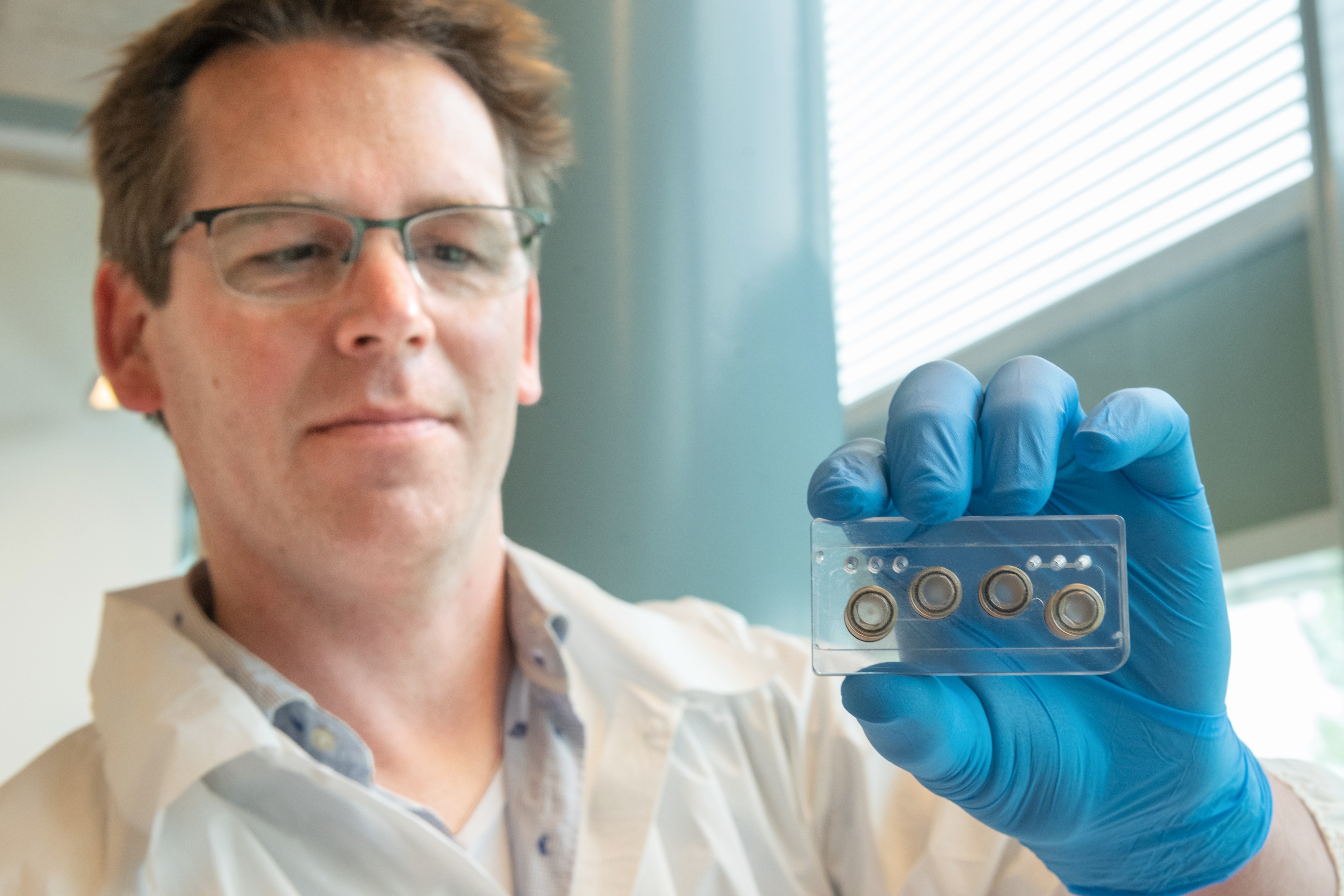

We’re using a new technology to do this research, the multi-organ-on-a-chip.

These are laboratory setups that model mini-versions of human organs. I do a lot of research on kidneys. We use diabetic nephropathy, kidney damage, as a model disease, and try out experimental therapies for it. The idea of the project is to study the repair of the kidney and the influence of interactions it has with the liver and pancreas. This can make a valuable contribution towards translatability of this therapy to humans. And, of course, to replacing the use of animals.

What did the financial support from the 3Rs Stimulus Fund mean to you?

It was invaluable. We were able to purchase an expensive machine, which we couldn’t have envisioned having before getting that support. Also, the chips we put the mini-organs on are pricy and can only be used once. This initial support has worked as a catalyst as well: after the 3Rs Stimulus Fund grant, we got a joint grant from the Samenwerkende Gezondheidsfondsen, Health~Holland, NWO, the Kidney Foundation and the Dutch Society for the Replacement of Animal Testing (Stichting Proefdiervrij) to expand this research. So this 3Rs support has given us quite a lot of spin-off. We’re now in the phase of publishing the results, with the caveat that we’re really making progress in the kidney-liver combination, but we’re setting the pancreas aside for now.

So professionally you’re enthusiastic. Do you feel personally involved as well?

I’ve never enjoyed doing experiments on animals. It involves an annoyingly huge amount of paperwork, but more importantly, it’s no fun deliberately making animals sick. Then you have to go there and check how they’re doing. And ultimately you have to kill them. So I’m happy that the government is encouraging people to develop as many alternatives to using animals as possible. I like to help spread the word about it. I incorporate that in my teaching, and the blogs I’ve been writing for a while for The Dutch Society for the Replacement of Animal Testing are a help too.